Shlomo Ben Adret

01/31/2019 06:24:40 AM

Dr. Mariana Montiel

| Author | |

| Date Added | |

| Automatically create summary | |

| Summary |

Shlomo Ben Adret (1235-1310), also known as RASHBA (RAbbiSHlomoBenAdret), was the most celebrated scholar of Jewish Law of his time. He was born in Barcelona, home to important medieval Jewish personages, although none as renowned as Shlomo Ben Adret.

Nachmanides (Moshe ben Nahman- Sephardic Corner 7), was his teacher and Ben Adret eventually substituted him as director of the Talmudic Academy.

Rashba actually was financier to King Jaime I in his younger years, although he left this activity to dedicate his life to Jewish Law, acting as Chief Rabbi of Barcelona during almost 50 years. Indeed, he served three kings as head of Jewish affairs, and his influence was so great that they were known to change opinion after listening to the discourses of Ben Adret.

Rashba actually was financier to King Jaime I in his younger years, although he left this activity to dedicate his life to Jewish Law, acting as Chief Rabbi of Barcelona during almost 50 years. Indeed, he served three kings as head of Jewish affairs, and his influence was so great that they were known to change opinion after listening to the discourses of Ben Adret.

He founded his own Talmudic academy where he exhibited copies of the Talmud originating from Babylonia to students who arrived from as far away as France, Germany, Italy, and even Palestine.

The interpretation of the Talmud often caused confusion and doubt. To find answers to the questions that would arise, rabbis and congregations would send their questions to a renowned scholar who would dictate the norms. These answers actually created a literary genre known as the responsa in Latin, and the Sheelot u-Teshuvot in Hebrew.

The volumes of responsa let us understand many aspects of Jewish life, as they contain the solutions to doubts about such subjects as personal ethics, morality, ritual practice at home and at the synagogue, Holy Days, how to express mourning or extreme joy, or the correct way to act at the workplace. Intellectual concerns were also addressed, and there are responsa that address religious philosophy, history, geography, mathematics, and astronomy, as well the interpretation of events in the Torah and the Mishna. The responsa are a precious source of historic information related to the daily life, and the religious and social reality of the Jews, at the moment they were written.

Through his reponsa, Ben Adret played a fundamental role in the organization of the Jewish communities and their institutions all over the world. Apart from being a Halachist, Rashba was knowledgeable in Greek philosophy and science. Indeed, the decisions and explanations of Ben Adret were a prime source of the book Shuljan Aruj, written by Yossef ben Efrain Caro, originally from Toledo but, after the expulsion, settled in Safed.

Even though Ben Adret was a traditionalist and believed in the literality of the Torah, he was an enemy of mystical interpretations. He censured the activities of Abraham Abulafia; however, he also censured those that belittled the study of the Torah, preferring science.

In the Anathema of Barcelona of 1305, Ben Adret formalized his position against those following the teachings of the great Maimonides (a future protagonist of our Sephardic History), who promoted the teaching of Greek metaphysics and physics. However, Rashba actually defended Rambam (Maimonides) in many debates about his work, and authorized a translation of Maimonides’ commentaries on the Mishna.

Nevertheless, Rashba was opposed to the philosophic-rationalistic approach to Judaism often associated with Maimonides, and he was part of the beit din (rabbinical court) in Barcelona that prohibited men younger than 25 from studying secular philosophy or the natural sciences (although an exception was made for those who studied medicine). Rabbi Yedaya ha-Penini of Provence, in his Apologetical Letter, refutes Rashba´s ban and questions the imposition of the Rabbis of Barcelona, while defending the scholars of Provence and the need of freedom to study the classics and all science.

Our only goal here is to show the profound and multi-layered aspects present in the intellectual debates of the time, without taking any stand, as both sides defended their perspectives with compelling and brilliant arguments. The conservative and normative approach of Ben Adret, materialized in a formidable collection of Laws about applications of the sacred texts in everyday life, needs to be understood in terms of his historic moment, and in light of the need to guarantee the continuity of the Jewish people in environments propitious to their extinction. His judgments have been studied in Talmudic academies for centuries and continue to be consulted by religious Jews worldwide. He is, without a doubt, one of the most influential Iberian scholars of all times.

The modern Jewish community in London was established by Sephardim in England in 1656, when the Jews were invited to return (they were expelled in 1290), and over the years this congregation attracted many Marranos from Spain and Portugal, fleeing the Inquisition. London also became an attractive alternative for many Sephardim established in Italy and Amsterdam, and several members of the community gained prominent positions in English life, for example, Moises Montefiore (Sephardic Corner 7) or Benjamin Disraeli. The Sephardic community thrived and built its first Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue at Bevis Marks in London, in 1701.

As an anecdote, we know that fried fish was introduced to the British Isles by Jews from the Iberian Peninsula, where it was called pescaíto frito. Thomas Jefferson, when passing through London, wrote a letter in which he praised the serving of fish cooked the “Jewish way”. Thus, the origin of England´s famous Fish and Chips can be traced to Sephardic Jews from the Iberian Peninsula!

Our post-expulsion protagonist is Grace Aguilar, (1816-1847) born to descendants of Conversos from the Iberian Peninsula who fled to England, escaping from the Inquisition and determined to return to Judaism. Her father, Emanuel, was a lay leader at the Bevis Marks synagogue, where the family was active in the Sephardic community.

When Aguilar was twelve, her father came down with tuberculosis and the family went to the coast in Devon, to reestablish his health. Her father used his time to educate his daughter in Jewish history. He related the “oral history” of the Crypto-Jews, who had pretended to convert to Catholicism to escape the Inquisition, but continued to practice Judaism in secret. She later used these stories for her historical romances, and her father served as her secretary.Indeed, when fifteen she started writing a historical romance situated during the Spanish Inquisition. Her novel, The Vale of Cedars (the Martyr) took her four years to complete and was published only posthumously in 1850.

The family began to suffer economically, and Aguilar began to think of making a career as a writer. Despite her own illness Aguilar, at twenty, began a cascade of literary production. In 1836–1837 she drafted the manuscript of her domestic novel Home Influence: A Tale for Mothers and Daughters, as well as its sequel, A Mother’s Recompense, and the novel, Woman’s Friendship.

In the late 1830s she also wrote the liturgy, meditations, and sermons that later appeared posthumously in 1853 as Shabbath Thoughts and Sacred Communings.

In 1838 her father asked her to translate Orobio de Castro’s (future protagonist of our Sephardic History) Israel Defended, from French, and he offered once again to serve as her secretary!

In 1840 Aguilar contacted Isaac Leeser, American rabbi, hazzan, and editor of the Jewish publication, The Occident. He decided to publish The Spirit of Judaism, her first important work, but the manuscript was lost at sea! Grace reproduced it from her original notes, and the book was finally published in 1842.

Aguilar began a constant collaboration with Leeser. From 1843 and during the remainder of her life, he published over thirty of her poems in The Occident, including Vision of Jerusalem and The Wanderers, a midrash on Hagar and Ishmael, generally recognized as her most successful poem.

In 1844, Grace wrote The Women of Israel, a series of biographical tales of biblical, Talmudic, and modern Jewish women. The critics recognized this work as her masterpiece, as she centered Jewish history and midrash on women’s experience, articulated her own versions of domestic ideology and theology, and appealed for Jews’ emancipation and Christian social acceptance.

In 1845 her father was dying and her own illness became increasingly severe. Under this pressure she wrote The Jewish Faith, presented as letters on immortality from an old woman to a young woman. In the same year, 1846, she was commissioned to write The History of the Jews in England. This essay was published months before her death, deals with Jewish-Christian relations, and is where she pronounces her rejection of assimilationism.

In 1847 she went to Frankfurt, where her musician brother Emanuel thought she might recover her health. However, she died that same year at thirty-one, and her death was called “a national calamity” on the front pages of Jewish newspapers in England and the United States. She was called “the moral governess of the Hebrew family” and Jews from France, Jamaica, and Germany wrote tributes and poems in her commemoration.

Sat, July 27 2024

21 Tammuz 5784

Worship Services

Coming Soon at OVS

-

Thursday ,

AugAugust 8 , 2024Splatter & Schmooze

Thursday, Aug 8th 6:00p to 8:00p

Unleash your inner artist, get to know other young adults, and make a masterpiece to take home. After splatter painting, there will be an optional After Party at Battle & Brew next door. For young adults up to age 40. Standard Price $36. Optional After Party not included. -

Sunday ,

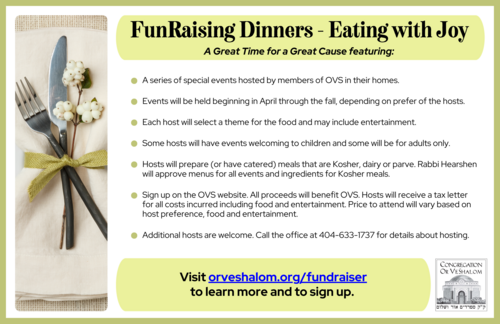

AugAugust 11 , 2024FunRaising Dinner - Clare and Robert Habif

Sunday, Aug 11th 6:30p to 8:30p

Join us for a Cuban dinner hosted by Clare and Robert Habif. All proceeds benefit OVS. -

Tuesday ,

AugAugust 13 , 2024Tisha B'Av

Tuesday, Aug 13th 8:00a to 10:00a

We will be observing Tisha B'Av on Monday, August 12 and Tuesday, August 13. -

Sunday ,

AugAugust 18 , 2024Welcome Back BBQ 2024

Sunday, Aug 18th 4:30p to 6:30p

Join us for a congregational welcome back BBQ at the Hearshen's house. RSVP by Monday, August 12. Park at OVS and take the shuttle bus. -

Sunday ,

AugAugust 25 , 2024Mitzvot Auction 2024

Sunday, Aug 25th 5:00p to 7:00p

Join us for our annual Mitzvot Auction and Keftes Dinner on Sunday, August 25 from 5:00 - 7:00 pm. Now featuring a live band of OVS musicians including Rabbi Hearshen, David Falkenstein, Hal Rabinowitz and Graham Levitas, a professional auctioneer and online purchasing. Dinner is $20 for adults, $5 for children ages 3-12. Children under 3 are free. Complimentary Childcare with advanced registration. -

Monday ,

SepSeptember 2 , 2024Apple Picking and Picnic Lunch

Monday, Sep 2nd 10:30a to 12:30p

Join us for a fun morning of picking apples for Rosh Hashana, visiting the petting zoo and more. Bring your lunch and join us for a picnic. Caravan from OVS at 9:00 am or meet at the orchard at 10:30 am at 9131 Highway 52 East, Ellijay, Georgia 30536. Members and non-members welcome. Participants will pay the orchard directly for entry and apples. -

Sunday ,

SepSeptember 8 , 2024Building Blocks Sunday School

Sunday, Sep 8th 10:00a to 12:00p

Building Blocks Sunday School at Congregation Or VeShalom is for children nursery age through 5th grade. Learning will focus on Sephardic Jewish heritage, holidays, Hebrew, and Israel education will be infused into the program. -

Sunday ,

SepSeptember 8 , 2024OVS Sisterhood Mezuzah Making Workshop

Sunday, Sep 8th 4:00p to 5:30p

OVS Sisterhood will join Rabbi Ruth Abusch-Magder and MACoM for Art and Uplift. Create a unique mezuzah to take home. $18 per person. Mezuzah parchment available for purchase. -

Sunday ,

OctOctober 6 , 2024Field Day 2024

Sunday, Oct 6th 11:00a to 5:00p

Intergenerational Field Day, including Tashlich service, will be held at Camp Ramah Darom. Registration fee includes gourmet lunch, snacks, a boxed dinner to take home and all activities. $18 per person.

Burekas & Biscochos

The Sephardic Cooks

My Preferences for Contact

Today's Calendar

| Shacharit : 8:46am |

| Mincha/Maariv : 7:40pm |

| Havdalah : 9:17pm |

This week's Torah portion is Parshat Pinchas

| Shabbat, Jul 27 |

Candle Lighting

| Shabbat, Jul 27, 8:23pm |

Havdalah

| Motzei Shabbat, Jul 27, 9:17pm |

Shabbat Mevarchim

| Shabbat, Aug 3 |

OVS Feature Video